Beacons of hope: Cleveland’s church steeples light the night sky

East Cleveland dentist Reinhold “Ray” W. Erickson always enjoyed the scene when he drove along Interstate 71 between Hopkins International Airport and downtown Cleveland.

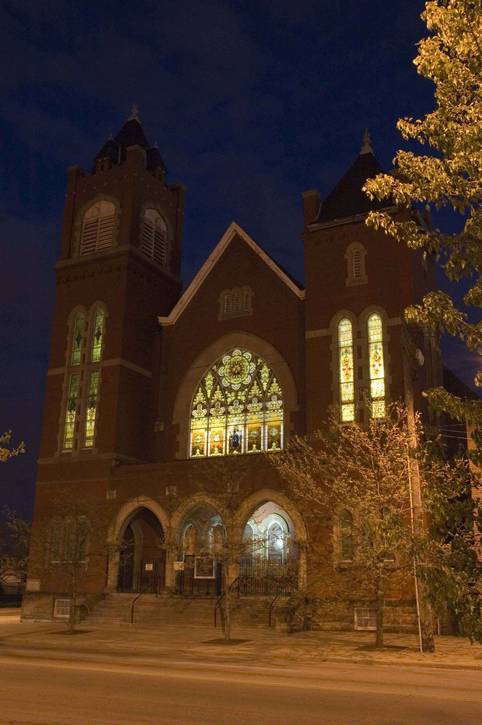

In the daylight, Erickson and other drivers could see the steeples, towers, and domes on the many churches that anchor the neighborhoods flanking the highway, but at night they became invisible.

The Old Stone Church (First Presbyterian Church)Erickson thought those churches should be illuminated so they could be appreciated day and night.

The Old Stone Church (First Presbyterian Church)Erickson thought those churches should be illuminated so they could be appreciated day and night.

Although he wasn’t a religious man, when Erickson died in 1992 at age 87, he donated his life savings—$370,000—to the Cleveland Foundation with instructions that the church steeples, domes, and towers visible from I-71 be lit, with any remaining money to be used for dental education.

Erickson’s bequest was one of the Cleveland Foundation’s earliest donor-directed initiatives. Because the organization, at the time, was not set up to directly carry out projects like Erickson’s, foundation officials contacted nonprofit historic building preservation organization, Cleveland Restoration Society (CRS), about taking on the project. CRS accepted the challenge.

“Dr. Erickson’s vision was that people go to Europe to look at the great cathedrals, but we have great cathedrals right here in Cleveland,” says Kathleen Crowther, CRS president and executive director. “He felt this was a great opportunity to highlight Cleveland’s diverse religious architecture.”

After three decades of illuminating Cleveland’s sacred skyline, the unique initiative to light church steeples along I-71 has been completed—leaving behind 24 brilliantly lit beacons of hope across the city’s neighborhoods.

The Steeple Lighting Program, which began in 1995 through Erickson’s bequest, has not only transformed the city’s nighttime landscape, it has helped preserve 24 historic religious structures.

“For an organization like ours, over a 30-year period, to have lit 24 steeples, towers, and domes is a massive amount of work,” says Crowther. “These lit steeples are dramatic punctuations of the night sky, and they can be quite memorable and spark conversations.”

The first building lit was Pilgrim Congregational Church in Tremont, with the project running from 1995 to 1998. Pilgrim underwent two lighting installations as the program refined its approach. Over the course of the program, CRS worked with two lighting designers: John J. Kennedy (now deceased) and David Kinkaid.

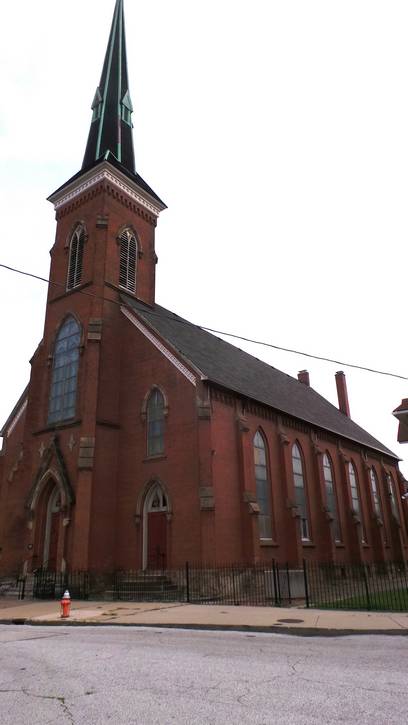

St. Patrick Catholic ChurchThe final project was completed earlier this year with Iglesia Pentecostal El Calvario, also in Tremont. The project presented challenges and delays due to language barriers, building maintenance problems, and financial shortages.

St. Patrick Catholic ChurchThe final project was completed earlier this year with Iglesia Pentecostal El Calvario, also in Tremont. The project presented challenges and delays due to language barriers, building maintenance problems, and financial shortages.

“Iglesia Pentecostal El Calvario became our hardest project to do,” explains Crowther. “They were raising money by selling tacos and refried beans on Saturdays, [but] they just were unable to keep up with the building maintenance. So we had quite a bit of structural work and repair that needed to be done.”

Between completing Pilgrim Congregational in 1998 and Iglesia El Calvario in 2025, CRS illuminated 22 other churches across the city—from the Detroit Shoreway, to Tremont, to downtown Cleveland—with each structure presenting a unique set of challenges.

“These lit steeples mark these places as beacons of hope in city neighborhoods,” Crowther points out. “People become happier, more positive, more hopeful if they can see that lit spire from their window or as they’re walking on the street at night. They know that this… isn’t a dark, gloomy, cold, stone place—it’s beautifully lit.”

Crowther adds that all the churches are lit with white light for a consistent artistic effect. “The white light just seems apropos for that type of building,” she says.

The steeple lighting program provided an added benefit to the churches: it gave the congregations an opportunity to inspect the towers for structural integrity.

“One thing we learned early on is that steeples, towers, and domes are very high places, and they’re places that congregations might not always be able to inspect for deterioration,” Crowther explains. “A really beneficial aspect of this program is that we were inspecting the physical structure of those steeple towers and domes.”

Each project presented unique challenges, from structural repairs to lighting design considerations. “It ain’t no walk in the park,” Crowther notes. “We were always working first to consider a lighting design that has beauty for the viewer to experience. All of these different buildings have different shapes and different ways to show off their decorative exterior features.”

The program cost approximately $600,000 in hard expenses over its 30-year run, covering repairs and lighting installation. Congregations contributed varying amounts to their individual projects and assumed responsibility for ongoing electricity costs.

St. Coleman Catholic ChurchWhile and CRS officials, technicians, and the churches never set out to measure economic impact, Crowther says she believes the lighting has contributed to neighborhood revitalization.

St. Coleman Catholic ChurchWhile and CRS officials, technicians, and the churches never set out to measure economic impact, Crowther says she believes the lighting has contributed to neighborhood revitalization.

“It goes to the quality of life of a neighborhood that does attract investment,” she says. “If you are a developer looking around to redevelop a historic building, build a new project somewhere... you’re going to say, ‘Oh, this is a safer place; this is a more interesting place.’”

The program’s legacy extends beyond aesthetics. “In the city of Cleveland, religious institutions are vital to the continuation of education and social services in neighborhoods,” Crowther notes. “We need to do everything we can as a collective community to keep their buildings in shape so they can continue their mission.”

The lit steeples have become such a distinctive part of Cleveland’s identity that Destination Cleveland has created a visitor’s passport featuring the illuminated towers and domes as a cultural attraction.

“If Dr. Erickson could ever be risen from the dead,” Crowther reflects, “I think he’d say, ‘I did something pretty good with my money.’ It’s sending out a lot of happy vibes all over town.”

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2025 issue of Sacred Places, the magazine of the Philadelphia=based Partners for Sacred Spaces, the only national, non-sectarian, nonprofit organization focused on building the capacity of congregations and communities to preserve and make the most of historic sacred places. We help faith communities better serve their towns and neighborhoods, transform their spaces for the future, and shape vibrant, creative communities. Republished with permission.