The wait is over: Warner & Swasey redevelopment secures full funding, set for January groundbreaking

After nearly four decades of vacancy and more than seven years of planning, Cleveland’s historic Warner & Swasey complex is officially on track for a transformative rebirth.

The building has become a canvas for many street artists in the past 40 years.On Friday, Dec. 5, officials with Pennrose Development, a Philadelphia-based developer with a Midwest office in Cincinnati, and MidTown Cleveland announced they have closed the final financial gap for the long-awaited adaptive reuse project, clearing the way for construction to begin in January.

The building has become a canvas for many street artists in the past 40 years.On Friday, Dec. 5, officials with Pennrose Development, a Philadelphia-based developer with a Midwest office in Cincinnati, and MidTown Cleveland announced they have closed the final financial gap for the long-awaited adaptive reuse project, clearing the way for construction to begin in January.

“This is a big day today—we have officially closed the gap," says MidTown Cleveland executive director Ashley Shaw. "We've got 24 sources helping us close on this project, which is the most many of us have ever seen on a single project. And we are now sprinting towards a December 15 full financial closing, which will be the closing date for the project.”

The $64 million redevelopment will transform the abandoned, decaying building into 140 mixed-income apartments and commercial space in two phases, while preserving the architectural character of the 1910 structure.

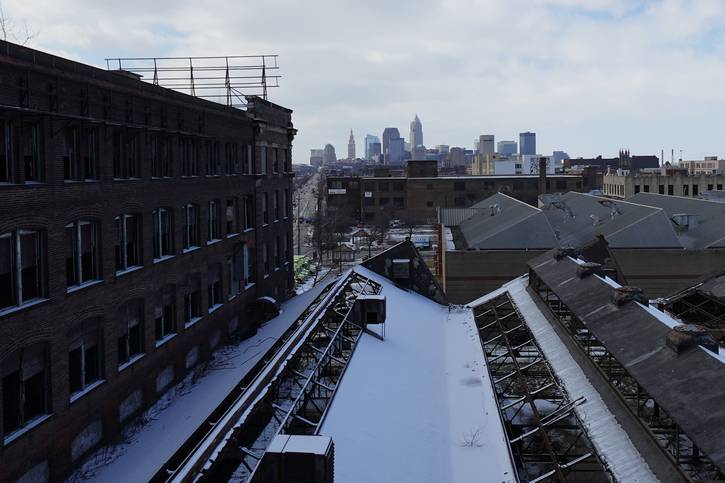

The milestone marks a turning point for one of MidTown’s most recognizable industrial landmarks—a 194,000-square-foot former manufacturing complex that has sat empty since 1985. Pennrose acquired the building in October from the City of Cleveland.

The original three-story, brick 19th-century revival-style building at 5701 Carnegie Avenue near the corner of East 55th Street was built by partners Worcester Warner and Ambrose Swasey in the late 1880s for Warner & Swasey machine tool shop, which specialized in turret lathes to make brass plumbing parts and other precision instruments.

Workers on the shop floor of the Turret Lathe Assembly Department at Warner & Swasey Co., ca. 1912In 1904, Warner & Swasey was so successful that the founders tore their original building down and hired renowned architect Arnold Brunner to design a five-story, 220,000-square-foot brick factory with a sawtooth roof. That building, completed in 1910, is what stands today.

The mid-1960s marked the beginning of Warner & Swasey’s decline. By 1980 Bendix Corp. bought Warner & Swasey, which ultimately launched the abandonment of the Carnegie building in 1985, followed by large layoffs, several acquisitions, and eventually the closure of Warner & Swasey’s remaining facility in Solon in 1992.

Meanwhile, the massive factory at 5701 Carnegie sat vacant for the past 40 years. Although the building became a canvas for many street artists in that time, it was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 2019.

Transforming a beloved landmark

For years, residents, former factory employees, and passersby have wondered when the building would find new life.

Warner & Swasey building circa 1941 from the west“I get asked every day, sometimes multiple times a day, what’s happening with this building,” says Shaw. “This milestone belongs to everyone who helped keep the spirit of this building alive: The former employees and families who preserved its stories, the civic leaders who championed its future, and the many partners who pushed alongside us to make this day possible.”

Since 2017, Pennrose and MidTown Cleveland, along with national architecture firm Moody Nolan, Cleveland-based John G. Johnson Construction, and historic preservation consultants Naylor Wellman, have been working through environmental remediation, extensive structural deterioration, and an intricate financing structure that includes the two dozen funding sources involved in what Pennrose development director Geoff Milz describes as "cobbling together the sources to make this project a reality” by the December closing.

“This project is a testament to how creative solutions can preserve community assets and deliver meaningful housing opportunities,” says Milz.

The industrial past creates challenges

The Warner & Swasey complex comprises the five-story Carnegie building fronting Carnegie Avenue and East 55th Street, with an attached Wedge Building abutting the railroad tracks.

A sawtooth-roofed portion of the building will be demolished to create on-site resident parking.Decades of exposure have left the building in severe disrepair. Milz explains that the factory’s original Cindercrete floors have deteriorated so extensively from water infiltration that they must be completely demolished and rebuilt.

A sawtooth-roofed portion of the building will be demolished to create on-site resident parking.Decades of exposure have left the building in severe disrepair. Milz explains that the factory’s original Cindercrete floors have deteriorated so extensively from water infiltration that they must be completely demolished and rebuilt.

Nearly all of the masonry requires major repair and tuckpointing, Milz says, and the building’s parapets—constructed with intricate engineering no longer common today—must be restored.

The building also requires metallurgical testing to determine how to safely weld modern steel to the facility’s original steel, which was manufactured using different processes more than a century ago.

“It’s been a long time since this type of steel has been produced,” Milz says. “It’s an unusual and fascinating challenge.”

Milz adds that some sections cannot be salvaged—like a sawtooth-roofed portion of the building, which will be demolished to create on-site resident parking.

An extraordinary funding partnership

Securing the financial structure for Warner & Swasey required what project leaders describe as a “herculean effort.” The 24 public, private, and philanthropic funding sources include federal and state tax credits, bank financing, historic preservation funding, brownfield dollars, affordable housing subsidies, and philanthropic investment.

“OHFA [Ohio Housing Finance Agency] was the last source in,” Milz says, noting that an additional 9% in tax credits were essential to closing the remaining gap. “We have officially closed the gap.”

MidTown Cleveland’s Shaw says the collaboration reflects the project’s importance. “Reviving Warner & Swasey with much-needed affordable housing not only preserves a cherished piece of Cleveland’s history,” she says, “it brings a landmark back to life and reactivates a vital gateway in our neighborhood.”

Decades of exposure have left the building in severe disrepair.A two-phased approach

Decades of exposure have left the building in severe disrepair.A two-phased approach

The redevelopment of the Warner & Swasey project will occur in two phases, with the first phase consisting of 112 units in the Carnegie Building. The second and third floors will have 56 senior housing units and floors four and five will be general occupancy and family housing. The units will serve households earning between 30% and 60% of Area Median Income (AMI).

The first phase will also include a second-floor rooftop terrace and other resident amenity spaces designed around preserved architectural features.

Phase two will center on that attached Wedge Building, which will be redeveloped into 28 workforce units that are not income-restricted.

The plan also includes approximately 22,000 square feet of integrated commercial space across the two buildings, encouraging neighborhood development projects and economic vitality.

While the project will provide quality inclusive housing that meets a need in MidTown, the upper floor apartments will provide skyline views of downtown Cleveland.

It’s all in the timing

The Dec. 15 financial closing deadline is dictated by regulatory requirements tied to many of the funding sources that include strict “placed in service” deadlines—requiring Pennrose to obtain certificates of occupancy within a 24-month window.

“We have some sources that require us to place the units in service by a certain date,” Milz explains. “It’s a very real deadline that drives the entire construction schedule.”

Worchester Warner (1846-1929), on the right, and Ambrose Swasey (1846-1937)Milz says construction will start immediately after closing, with site work launching in January. He says the heavy construction will begin in the winter months, with a public groundbreaking celebration planned for spring, when the weather should be more suitable for the large number of partners, supporters, and former employees expected to attend.

Shaw says the Warner & Swasey project is more than a redevelopment—it’s a restoration of community memory.

“This is a proud and deeply meaningful moment for our community,” she says. “Reviving Warner & Swasey with much-needed affordable housing not only preserves a cherished piece of Cleveland’s history, it brings a landmark back to life and reactivates a vital gateway in our neighborhood.